Searching for safe harbour

As families continue to migrate from northern Central America and Mexico, UNICEF is helping protect children on the journey and addressing the circumstances that lead to their quest

- Available in:

- English

- Español

Gang-related violence. Organized crime. Extreme poverty. All are a part of daily existence for millions of children in northern Central America – El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras – and Mexico. But as families make the difficult decision to pack up their lives and travel by car, open-air truck or foot, it’s crucial to remember that they all have one thing in common. They are humans, too – only humans in need.

Sadly, many families attempting to escape their desperate circumstances experience new traumas along migration routes, including long, uncertain journeys in which they face the risk of exploitation, violence and abuse. They may be apprehended in transit or upon reaching their destinations, detained and returned to the same problems – or worse – that drove them to uproot in the first place.

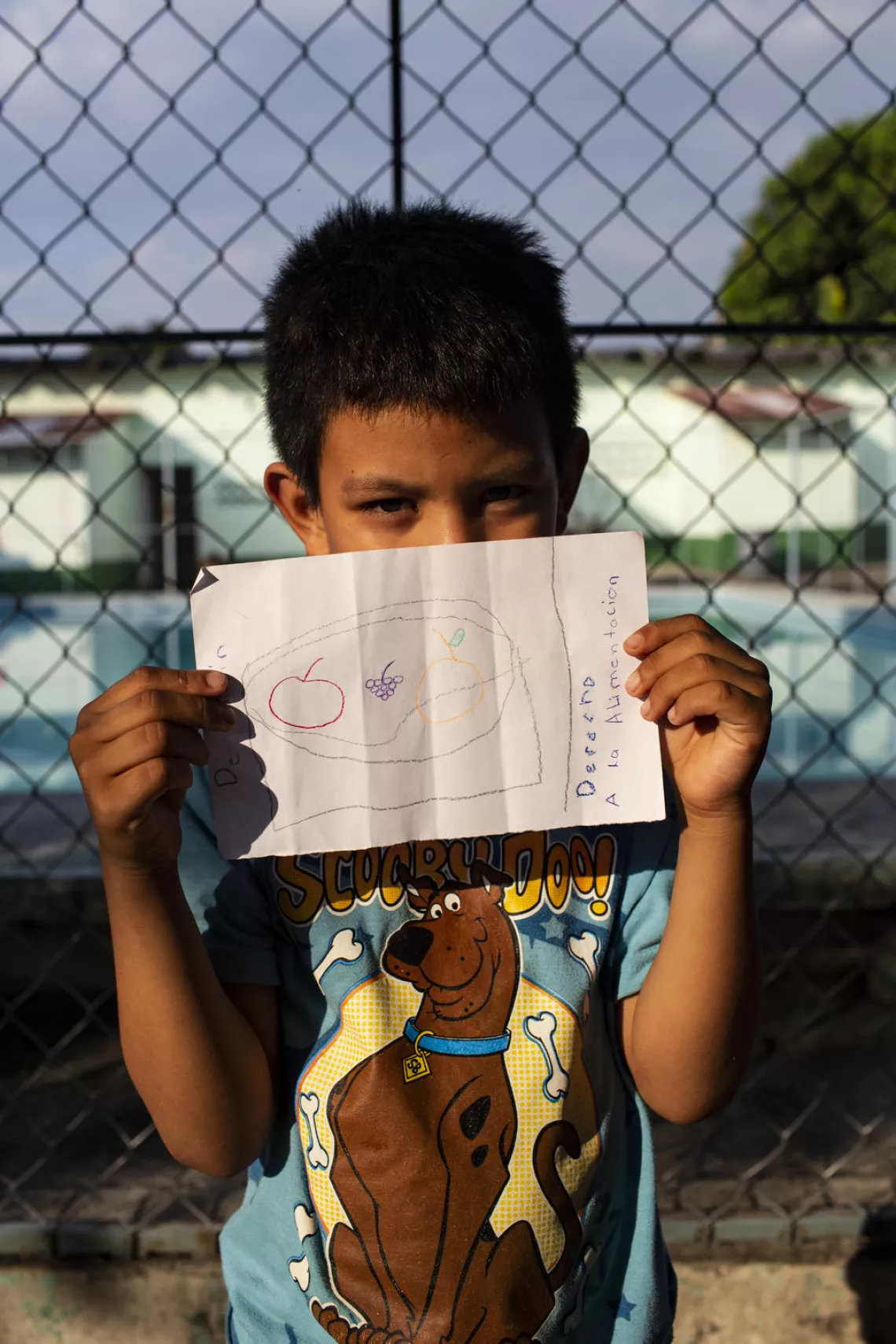

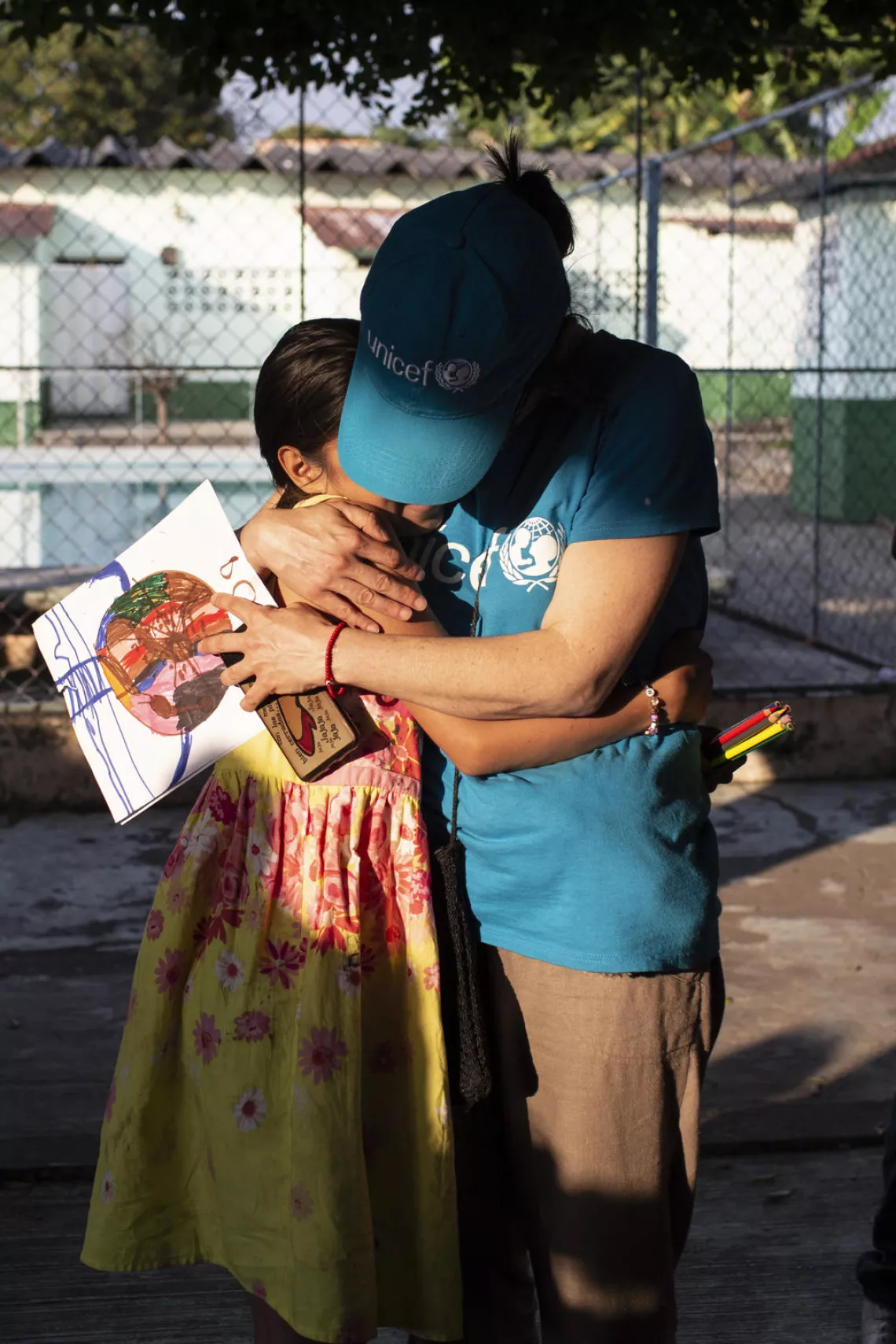

There exist proven approaches, such as the creation of safe spaces and educational, recreational and vocational opportunities that aid children in transit, as well as address some of the sources of irregular migration. While UNICEF continued to work with governments in January 2019 to mitigate the conditions that push families to leave their homes in search of safety and stability, its ultimate aim always remains: to protect children along their passage.

(Above) A mother is bathing her child as she waits for a fast-track humanitarian visa at the Mexico-Guatemala border in Ciudad Hidalgo, Mexico. While Mexico is increasingly implementing measures to safeguard children’s rights – such as the visa, which allows migrants to stay in Mexico, work and access social services – challenges persist. Around 68,000 children were detained in Mexico between 2016 and April 2018 – 91 per cent of whom were deported to Central America.

"We are fighting for our kids and their future."

"I feel like I have never been given the opportunity to achieve my dreams."